<<First Page of Series

<Previous Day

Mornings in the "mattress camp" come early -- with lots of zippers. Granted, there is plenty of zipping in the night, as folks slip in and out of their sleeping bags and stumble to the bathroom, headlamp beams thrashing wildly in the musty air. As they pass, others stir and, inevitably, someone else realizes they need to unzip.

But the morning zippers are far more aggressive. They begin usually around 5AM, when I am still hoping that I might snatch at least one hour of undisturbed sleep. It is then that the worst of the zipper-heads strike. "ziiiip..rustle-rustle... ziiip.. jingle, thwap, ziip..shick-shick-shick... bundle-bundle-bundle......ziiiiiiiiip... (repeat ad infinitum)" I have come to suspect that the main difference between a European "rucksack" and a North American "backpack" is that the rucksack has five times as many zippers.

Eventually someone turns on the lights -- usually around six -- undoubtedly to see his zippers more clearly. It is only my legendary self-restraint that prevents me from pelting this chief zipper-head with bits of leftover cheese and a toothbrush.

The only way to sleep soundly in a matratzenlager is to wear ear plugs and an eye mask. If, however, one's left ear plug has somehow fallen out during the night and slipped between two mattresses, there is no option but to rub one's burning eyes and join the early risers. Such was my situation at Memminger Hütte.

I was soon zipping up and down with all the other zipperheads, packing my bed linens and digging around for my missing ear plug. I then proceeded down the creaky wooden steps to the breakfast room where most of the tables were occupied by large parties. Again I picked up my breakfast which included no pleasant surprises, just the same old bread, jam, etc. that I had come to expect.

Charles had already eaten (or perhaps chosen not to) and was deep in conversation when I came outside to meet him. The man's name was Dietrich. He was a physically fit 40-something with substantial calves and a white baseball cap on his head. They were speaking in German but as I joined them they shifted easily to English. When I complimented his language skills he replied "No, my English is not so good. You should hear my son, his English is excellent and his French is even better."

"Then I look forward to meeting your son," I said.

I did not have long to wait. Robert, Dietrich's son, was a fourteen year old wunderkind. His English was, indeed, excellent -- even his accent was convincing. He was well-versed in history, science and pop culture and had an incredible thirst for all things "American".

Robert's mother, Haike, was young, attractive and energetic, with dark hair and a bright smile. She was not as talkative as Robert and Dietrich and often deferred to Dietrich when it came to hiking decisions. As a family unit, they were an impressive group. Dietrich was an admirable father-figure, handling maps with manly skill, carrying the lion's share of the load and, most impressively, still commanding the respect of his teenage son. Charles and I secretly began referring to them as the Übers. This was short for "Über Familie", our clandestine nick-name for this impressive little team.

We hiked across the bottom of the crater with the Übers and up the scree slope at the far edge of the bowl. Robert stuck close to Charles and me, peppering us with questions about the States. Although we could not tell him anything about his favorite band, KoRn, we did manage to fill him in on what it was like to live in Boston and Manhattan. We took turns entertaining him with stories of misspent youth and were both thankful for someone new with whom to pass the time.

The climb from the bottom of the canyon to the top of Seescharte, the needle's eye through which we would need to pass, was an arduous hour's hike. Charles and I both started out briskly to show that we could keep pace with a teenager -- of course, we could not. Dietrich and Haike started the climb more slowly, hanging back at first but eventually catching up with us as we huffed and puffed our way up the steep slope.

"You started too fast." Dietrich admonished us. "That is how you get so tired. If you start more slowly you do not have so much trouble next time."

He was right, of course. We soon came to realize that Dietrich was generally right about many things.

Just before Seescharte (the top of the pass) was a vertical scramble to a small rock-framed vista. Through the notch were another hundred miles of rough mountain silhouettes layered as far as the eye could see. The view was staggering.

We had realized that we would be hiking on the same schedule as the Übers all the way through to Bolzano. We were all quite happy to have more companions but, with so much time at our disposal, we split up as we hiked down the other side of the mountain.

It was not long before the ground leveled off in a large, lush plateau. We entered a muddy forest with towering conifers, like giant Christmas trees. The rich, muddy earth was pockmarked with the tracks of cows and horses. There were rivers to cross on bridges made from logs and scrap wood. The forest had an ancient, lived-in, feel to it, as if it had been carefully managed for centuries. The trees were well spaced, occasionally there was a stump where a tree had once stood. Then, after another river crossing, we discovered a green, mossy field, studded with small log cabins. It was like an enchanted village from a fairy tale -- no roads, no people, just well-built cabins in an idyllic setting. If we could have stopped, we might never have left.

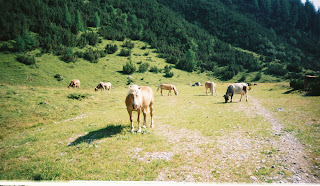

Soon the trees gave way to pasture land. In the field was a herd of blonde horses and cows and another small cabin encircled with a rough hewn log fence. In the

small enclosure was a picnic table and a trough with a faucet for drinking water. Charles remembered this cabin serving a decent snack, so I ordered us a cheese plate and two radlers.

small enclosure was a picnic table and a trough with a faucet for drinking water. Charles remembered this cabin serving a decent snack, so I ordered us a cheese plate and two radlers.The Übers stopped by but only briefly. We asked them if they would be staying in Zams and Dietrich answered that they were going to a hut just a few miles further. The Übers were exceptionally thrifty, as most Germans seem to be. They would hike through a swamp to save fifty dollars. Charles and I were quite the opposite. We found creature comforts too tempting to resist.

Our cheese plate was loaded with thick slabs of a white local cheese. It was smooth and came in round thick slabs, very much like a provolone. There was more cheese than bread and, looking around, the reason was obvious. There were cows all around and, ostensibly, plenty of milk. Bread, on the other hand would have to be brought up by ATV from the village several miles below.

After eating our fill, we packed up the leftover cheese and continued on our way. We soon found ourselves walking down a trail hewn into the side of a mountain on the left of a great, green gorge. The way was shaded and, through the cleft in the mountains, we caught glimpses of the town in the valley below. We were still at the height of an airplane, however, and the town was still miles away. What we thought was Zams turned out to be Landeck, and we realized our mistake as we rounded the mountain to the east.

The woods grew thickly on the south side of the mountain and our trial became a seemingly endless series of switchbacks over trails of sand and pine needles, each

turn bringing the streets of Zams just a hair closer. Half way down this leg we found a boulder with a plaque telling the story of Alois Bogner who met his end in these mountains, perhaps under this very rock, back in 1862. The boulder told his story in poetic detail, or so Charles informed me. If you read German, you can enjoy it for yourself.

turn bringing the streets of Zams just a hair closer. Half way down this leg we found a boulder with a plaque telling the story of Alois Bogner who met his end in these mountains, perhaps under this very rock, back in 1862. The boulder told his story in poetic detail, or so Charles informed me. If you read German, you can enjoy it for yourself.For some reason, this short walk was tiring us out. Our knees protested the relentless downward slope, as did our thighs. Seeing the town for so long in the distance was much harder than coming upon it by surprise. The first thing I would have was a Coke, I decided, and if we could find it, I wanted to eat pizza. I had lived far too long on German fare. We were close enough to Italy that I should be able to find something more rich in carbohydrates. I wanted the things that one takes for granted in any small town.

The trail finally spilled out on a dusty service road. We studied the map for a moment, then took a right on the road and a left, over a covered highway, protected from winter weather, to a quiet street at the edge of town. Someone had been kindly enough to actually erect a fountain for hikers. I filled my bottle but did not drink too deeply, saving my thirst for the Coke I had promised myself. From the mountain, the way to the center of town had seemed obvious but, once on the ground, it was more difficult to navigate. We looked at our map again and headed southeast, through quiet streets, then briefly due east, along a rushing turquoise river by the name of "The River Inn". The water, opaque and churning, was startling in color. This was probably the result of dissolved limestone but it looked distinctly minty to me.

We turned right (southeast again) onto a main thoroughfare, past a supermarket and several restaurants -- two with pizza! By 1:00 we were standing in the center of town, facing the ancient Postgasthof Gemse, operated by the Haueis family since 1726.

Inside we were met by a friendly old woman in a blue and white house dress. We requested two single rooms and she led us slowly up a broad, leaning, cantilevered staircase -- full of charm and beauty but nerve-wracking in its creaking and sagging. I would have moved more quickly if our hostess had not been leading the way. As it was, I hugged the wall.

The floors were covered with aging Oriental carpets, and the walls were decorated with a dozen or more heads of various horned beasts. Stuffed foul stood on mounted wooden perches, and pictures of mountain goats were interspersed with those of generations of Haueis mountaineers. All were photographed against dramatic backdrops which gave the impression of a vigorous and daring lineage.

The floors were covered with aging Oriental carpets, and the walls were decorated with a dozen or more heads of various horned beasts. Stuffed foul stood on mounted wooden perches, and pictures of mountain goats were interspersed with those of generations of Haueis mountaineers. All were photographed against dramatic backdrops which gave the impression of a vigorous and daring lineage.Our rooms were immaculate, mine with the Virgin Mary (no pun intended) in devoted prayer above the bed. I tossed my dirty pack in a corner and admired the clean, flat, sheets and show-white down comforter piled high in the center -- much too clean to enjoy until I had taken a good hot shower.

"I wish I had the Virgin Mary over MY bed," said Charles, after our hostess had departed.

"You can have my room if you want," I told him. He declined, and I was secretly happy that he did.

We found lunch in a grotto-style restaurant and I had my pizza and Coke. It was as delicious as I had hoped, and I stuffed myself without shame. I was convinced that I was losing weight and, not being a hefty guy to begin with, was a little concerned. After lunch we found a shoe store a half mile beyond the guesthouse. There I bought the most expensive shoes I had ever purchased, for a whopping $216. These hard-core trekking boots were made by Lowa and pretty much walked themselves. Once I tried them on, I knew I would blow the bank. My feet had never been so happy in my life.

We walked back to the guesthouse and parted ways. Charles went back to his room to read and relax, I walked to the nearby Esso station and asked the clerk if they sold pens. "Here," he said, handing me a nice new ballpoint. "You can keep it." It was a small gesture but endeared me still more to Zams. I returned to the ancient bar on the first floor of the guesthouse and ordered myself a weissbier.

I had intended to write postcards but was quickly side-tracked by a group of six hikers who were drinking at a corner table. They recognized me from the trail and asked if I wanted to join them for a drink. I agreed, and they all shifted to English for my benefit. Several spoke English quite well and, when I asked if this was common, they replied that it was quite common indeed. In fact, they told me, most every educated German under the age of forty has taken some English classes. If they are not fluent in English, they would be fluent in French. This was news to me -- very good news.

I had another beer and quizzed them about their jobs and where they were from. After an agreeable hour, I retreated to my room to finally take my shower. I promised to meet two of them, Kirsten and Werner, for dinner an hour later.

I checked in briefly on Charles but he was in a foul mood for reasons I would learn the next day. He declined dinner and retired again to his room.

The entire day was a blur of new friends, socializing and gluttony. We met at the agreed upon time at a tavern we had each seen on our way into town. It had the feel of a family-style restaurant and a menu that was easy to understand. I had pizza again and we continued our conversations about Germany, America and our experiences with each. Kirsten was the more fluent English speaker but Werner understood most of what was said. I found Werner engaging, regardless. He had a constant smile etched into his cheeks, and I had the impression that, if he could have expressed everything on his mind, he would have been a very entertaining companion.

It was nearly ten o'clock when I finally fell into bed. The sheets were cool and, with the breeze through the window and one leg uncovered, the airy down comforter was just the thing. I slept there like an innocent child with Mother Mary watching over me.

Next Week

Braunschweiger Hütte